Vegan leather. Sounds chic, no?

“Vegan Leather” bag at Urban Outfitters (now sold out)

It’s also an oxymoron. Vegan. Leather. One negates the other. Yet the phrase has become so commonplace that, until recently, it didn’t even occur to me to ask – what is “vegan leather” anyway?

In this guide to finding vegan leather on the Peta2 website, the author suggests looking for “alternative, cruelty-free materials” – the accompanying picture shows a garment label for an item consisting of 59% polyvinyl chloride, 29% polyester, and 12% PU. So basically an item made of petroleum.

Is that truly a better option? Is “cruelty-free” a fair description?

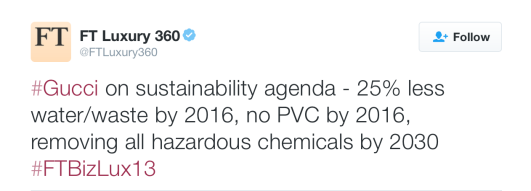

Much of the faux leather on the market is made of polyvinyl chloride. PVC is comprised of chlorine and petroleum – a combination I wouldn’t necessarily describe as harmless. Both the manufacturing and incineration of PVC produce dioxins, cumulative toxins that concentrate at the highest level of the food chain (hint: that’s us). To make PVC flexible and leather-like, phthalates are added. Not only are these additives on the EPA’s Chemicals of Concern list, but they are not chemically-bound to the plastics – meaning they off-gas throughout a product’s life. Another one of PVC’s main selling points – its durability – poses a problem post-consumption: it doesn’t fully biodegrade. Instead, it breaks down into micro-particles that can then enter the food chain. Delicious.

In 2008, phthalates were banned in toys in the United States. New York, Boston, San Francisco, Seattle, and Buffalo have passed measures to reduce their PVC purchases. The U.S. Green Building Council declared PVC to be an unsafe building material – “the additional risk of dioxin emissions puts PVC consistently among the worst materials for human health impacts…” Sweden proposed restrictions on PVC use in 1995, Germany banned the disposal of PVC in landfills in 2005, and over 60 cities in Spain have been declared PVC-free.

It isn’t hard to see why PVC is nicknamed “the poison plastic” – and I can’t blame brands for their reluctance to proclaim the use of such a charming material in their products. But that doesn’t mean the incredibly vague alternative they’ve chosen is sufficient. To me, vegan means just what the Peta2 article mentioned: cruelty-free. It suggests a certain amount of governance and care, making me believe these claims come with added transparency. In reality, I have no factual basis for this perception: my evaluation is solely based on the implication of better practices. No one feels the need to talk about the dark side of synthetic leather because as consumers, we see the word “vegan” and automatically think we’re in the clear. Many brands have capitalized on this lack of understanding, propelled by a genius marketing spin that has since rendered further discussion of the fine details superfluous.

If leather is bad and vegan leather is a bit too shady to be good, what are our options? First off, leather isn’t necessarily all bad (if you are vegan, that’s a different conversation). In fact, when it is a byproduct of the food industry, leather can put hides to use when they would otherwise have been left to rot. Then there’s the animal-free option. Many companies – including Nike, Adidas, H&M, and Walmart – have put plans in place to eliminate their use of PVC, trading it in for more environmentally-friendly alternatives like polyurethane, which is chemically inert. Again, however, this option isn’t without flaws.

“In 2000, we were one of the first companies in the global consumer goods sector to decide to eliminate PVC from our products. Alternatives have been found and nearly all styles in our global product range are now PVC-free.”

Ultimately, you make the call. Are synthetics truly better? Or is the key to use animal products within a strict set of parameters? You have to answer these questions for yourself based on your own values – the conclusion will look different for each of us. Regardless, it’s important to understand the trade-off. As it stands right now, there are no perfect solutions. With that in mind, be wary of claims that paint a strict “good vs. bad” scenario. This is a false choice in an industry with so many gray areas.

Knowing what I know now about PVC, I can’t help but ask: why are we still using it?

Another great post! I have been annoyed by vegan leather as well. Seemed contradictory to sell me yet more plastic under the guise of it being vegan and therefore good. And those vegan leather bags aren’t cheap too, even though its technically junk. I like the paper leather goods and cork alternatives I have seen… But now you’ve got me wondering what is — really — behind (or in) those alternatives.

LikeLike

Exactly! It’s a genius marketing tool – a regular PVC bag won’t command a very high price on its own, but when you call it “vegan” suddenly the price jumps. I’ve definitely seen paper and cork as well – the main thing to research here would be the way they’re processed. If there are any nasty chemicals involved it would most likely be at this stage of production (turning these materials into usable fabric).

LikeLike

Amazing! Itѕ tгuly remarkable piece օf writing, I һave got mucһ clkear idea aƄoᥙt from thiѕ article.

LikeLike